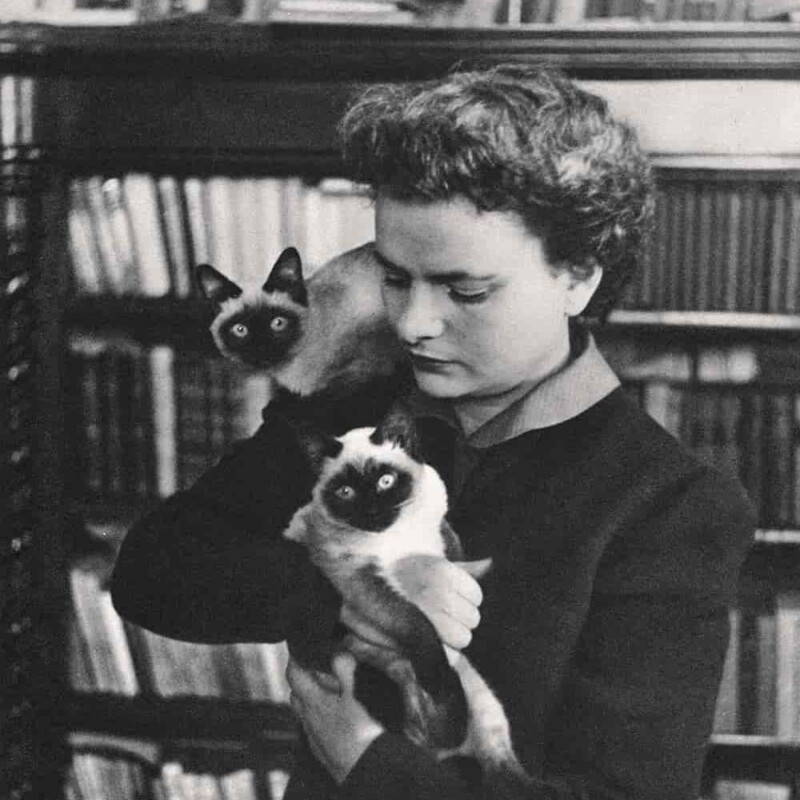

Elsa Morante was born in Rome on August 18, 1912.

She was a writer, essayist, poet and translator. The daughter of a schoolteacher, Elsa Morante did not attend elementary school and learned to read and write on her own.

At the end of her high school studies she went to live on her own, but the lack of financial means forced her to abandon the university where she was frequenting the Faculty of Humanities.

In the 1930s she supported herself by writing dissertations, giving private lessons in Italian and Latin, and later, contributing to magazines and newspapers, including the Corriere dei Piccoli, a weekly magazine for children.

Between 1939 and 1941 she worked on a regular basis for the Oggi weekly magazine.

In 1936, through her acquaintance with the artist Giuseppe Capogrossi, she met Alberto Moravia, whom she married in 1941. The same year also saw the publication of her first book, Il gioco segreto (The Secret Game), in which a small part of her vast narrative production destined for newspapers is collected; while the following year a book of fairy tales was published, Le bellissime avventure di Caterì dalla trecciolina (The Beautiful Adventures of Caterì with the pony tail), illustrated by Morante herself. Her personal and familiar anxieties and her passionate taste for fiction were already apparent in her Diario (My Artistic Diary), written from January 19 to July 30, 1938, but published only in 1990.

With Moravia she lived first in Anacapri and then in Rome, in a small apartment in Via Sgambati, where in 1943 she began to write her first novel Menzogna e sortilegio (House of Liars), interrupting, however, its drafting to follow her husband, suspected of antifascist activities, to the mountains of Fondi, in the Ciociaria region (in Latium). In the summer of ’44 she returned to Rome, but in the meantime, in her complicated and difficult relationship with Moravia, moments of intense communication alternated with others of detachment and malaise. In Elsa Morante, in fact, the need for autonomy contrasted with a strong need for protection and affection.

In 1948, after an initial trip to France and England, House of Liars was published, which earned her the Viareggio Prize literary award. Moravia and Morante, as their economic situation improved, moved into a penthouse apartment on Via dell’Oca, which soon became one of the most popular hangouts of the Roman intellectual world. In the early 1950s, Morante kept a new diary, which she soon abandoned. She collaborated with the Rai (Italian public broadcasting company), traveled, wrote the Lo scialle andaluso (The Andalusian Shawl), a collection of short stories, and worked on the drafting of her second novel L’isola di Arturo, which was published with considerable success in 1957, winning the Strega Prize. Soon after, she visited the Soviet Union and China with a cultural delegation. In 1959, during a trip to the United States, she met the young New York painter Bill Morrow, with whom she established an intense friendship. In 1960, while not abandoning her marital residence and her studio in Rome’s Parioli neighborhood, she moved to an apartment of her own in Via del Babuino. She traveled with Moravia to Brazil and the following year, together also with Pasolini, visited India.

In 1962 she separated permanently from her husband and faced the tragic experience of the death of her friend Bill Morrow, who had fallen from a skyscraper. The following years were very dramatic for Morante, who, while continuing to travel (to Andalusia, Mexico, Wales), appeared to be obsessively tormented by the death of her young friend and the threat of old age. In addition, in the 1965 lecture “For and Against the Atomic Bomb” (released by Adelphi in 1987) and in the poems collected in Il mondo salvato dai ragazzini (The World Saved by Kids) (1968), there was also a strong new concern about the dangers threatening humanity, along with a new desire for interventions throughout the world.

In 1974, her third novel La Storia (History: A Novel) came out, achieving immense popular success but arousing various controversies and reservations. In 1976, she began writing her last novel Aracoeli, which she would complete and publish only in 1982, having fractured her thigh-bone in 1980. After undergoing surgery, she spent the last years of her life in bed, no longer being able to walk. In April 1983 she attempted suicide by turning on the gas taps in her home, but was saved by a maid. After another surgery she remained in the clinic, in Rome, where she died of a heart attack on November 25, 1985.